The line between wilderness & tradition

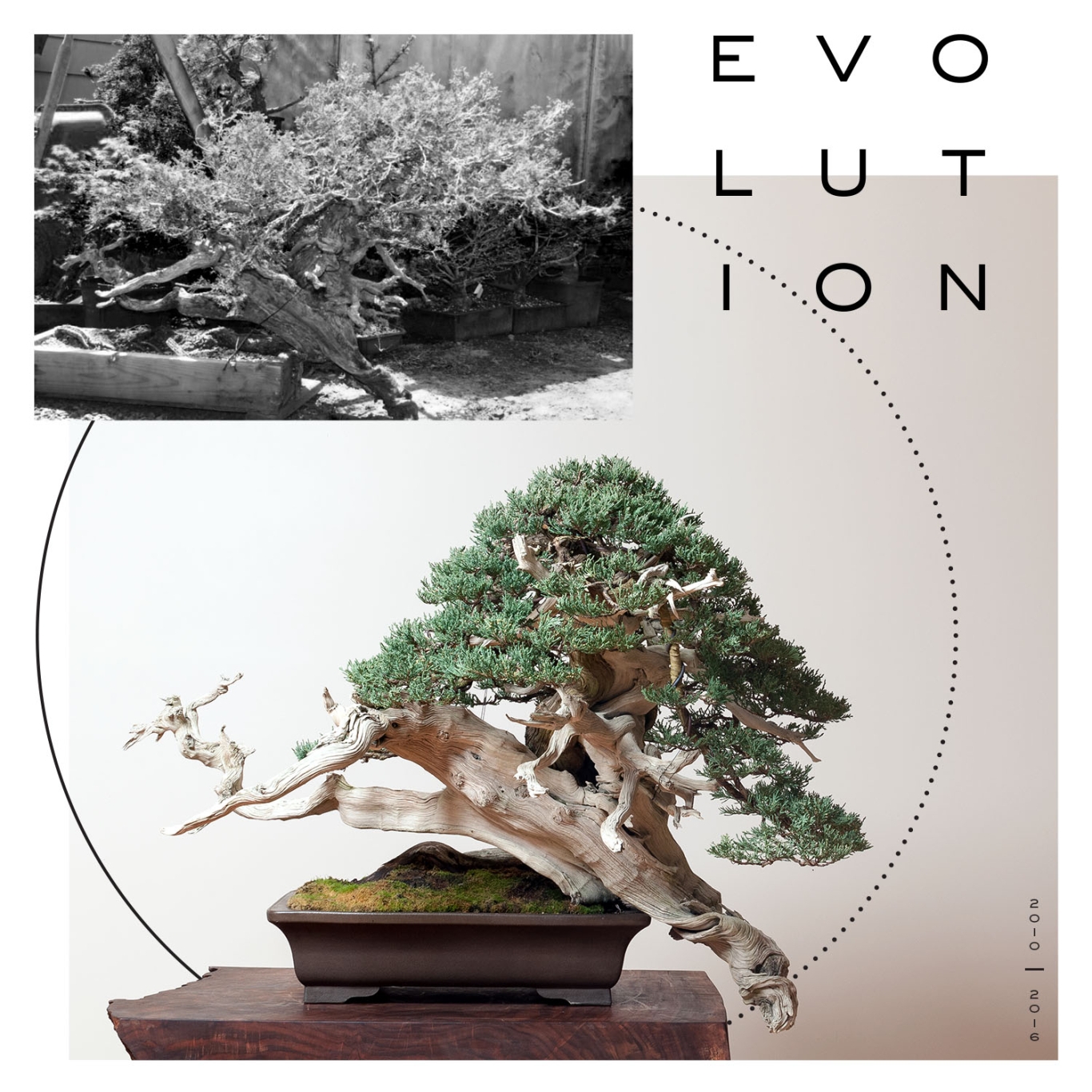

The first time I saw this tree was during my inaugural trip to Oregon to connect with Randy Knight. Randy obviously had a whole yard full of amazing material, but I came upon this Rocky Mountain Juniper. It looked like an ancient skeleton clinging to survival in this long wooden box, maybe no more than 6 inches wide, supporting this massive tree.

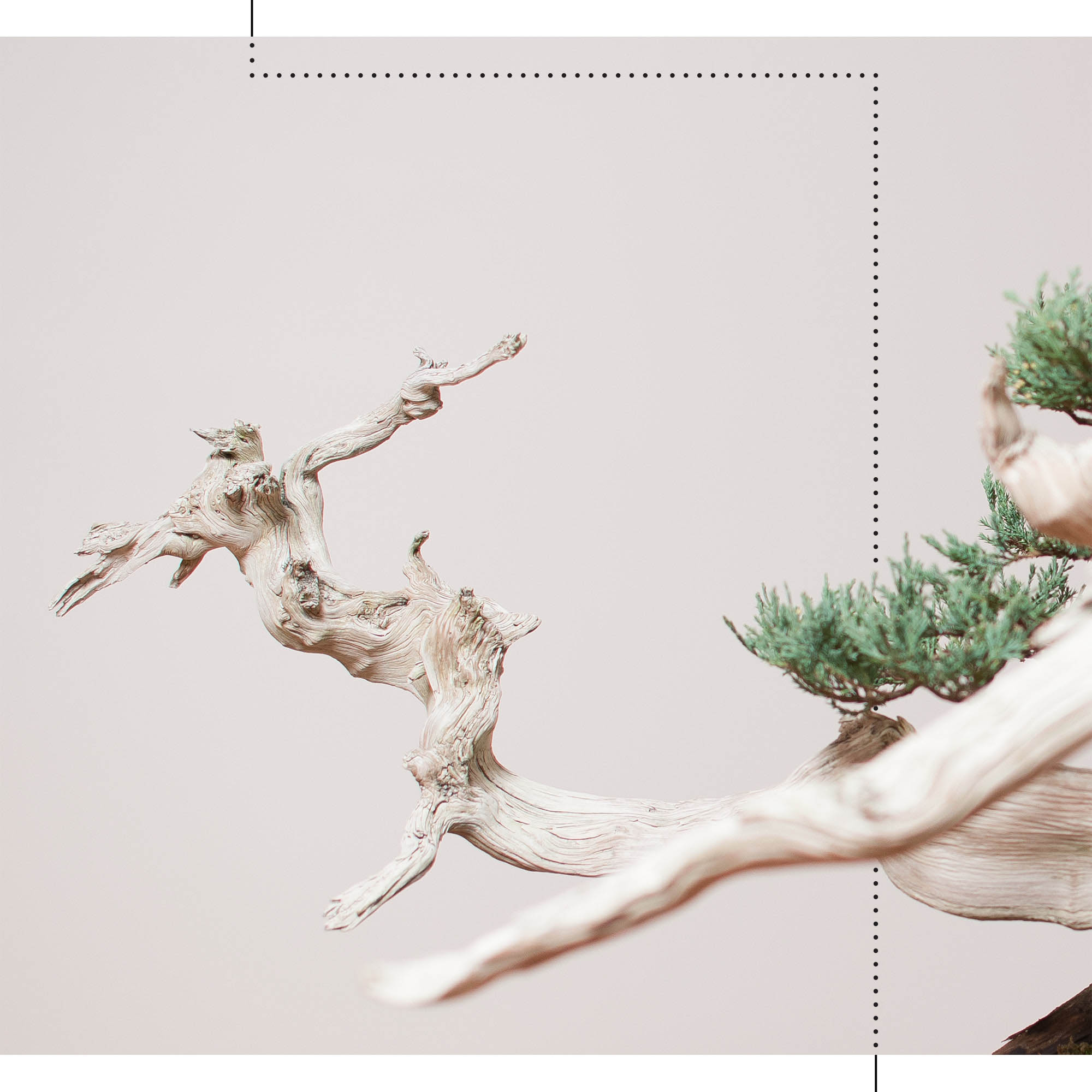

I had never seen anything like it. To this day I haven’t seen another Rocky Mountain juniper that displays so many insane characteristics—twisting deadwood, bright bluish foliage, wonderfully proportioned branches in all the right places. This tree epitomizes struggle and survival; it was meant to be a bonsai.

Randy made sure to let me know this was not a piece he was willing to part with. He knew how special it was and wanted it for his personal collection. I went back to Japan re-energized by the native trees I encountered. I was filled with a yearning to expand my bonsai knowledge so I could work with and elevate trees of such a caliber.

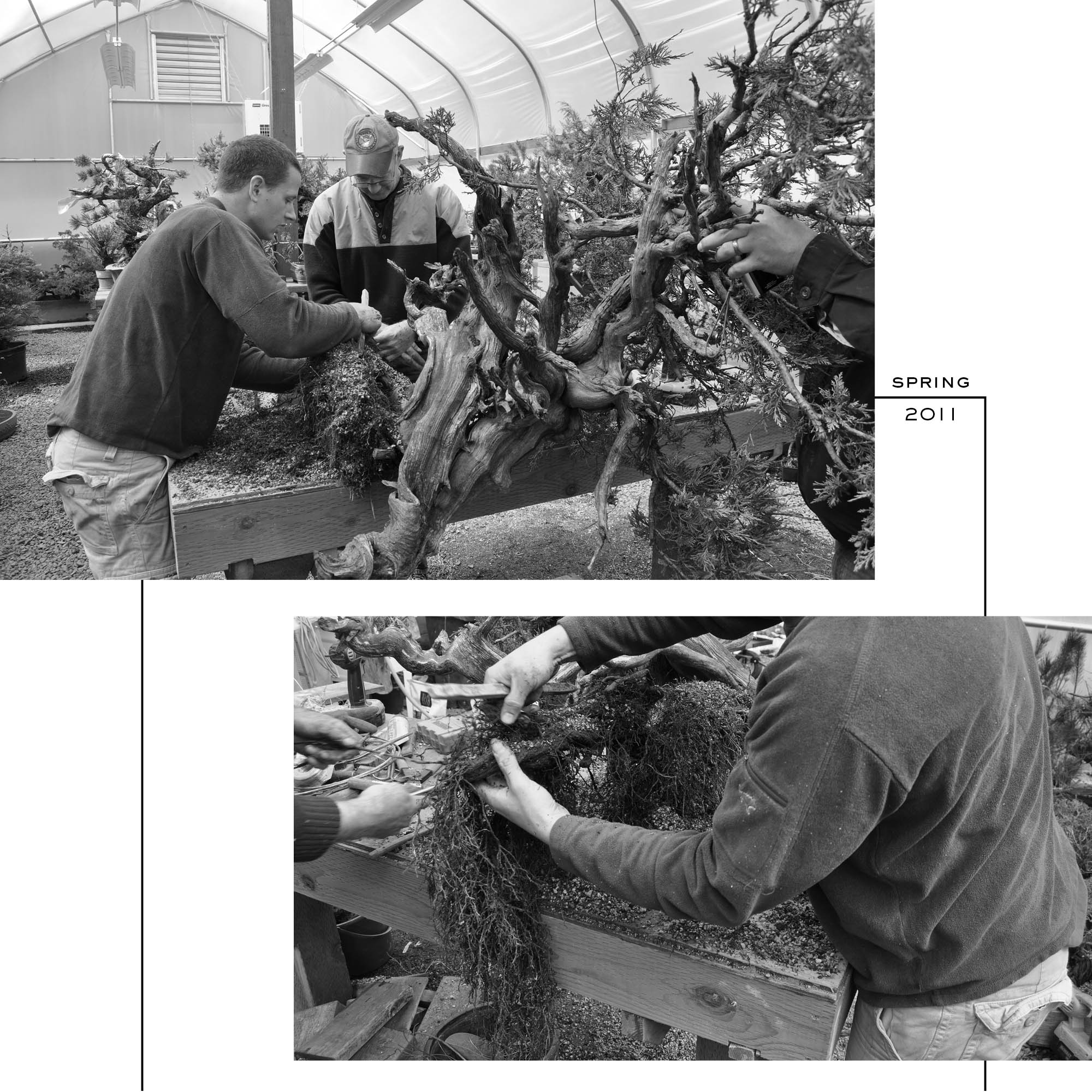

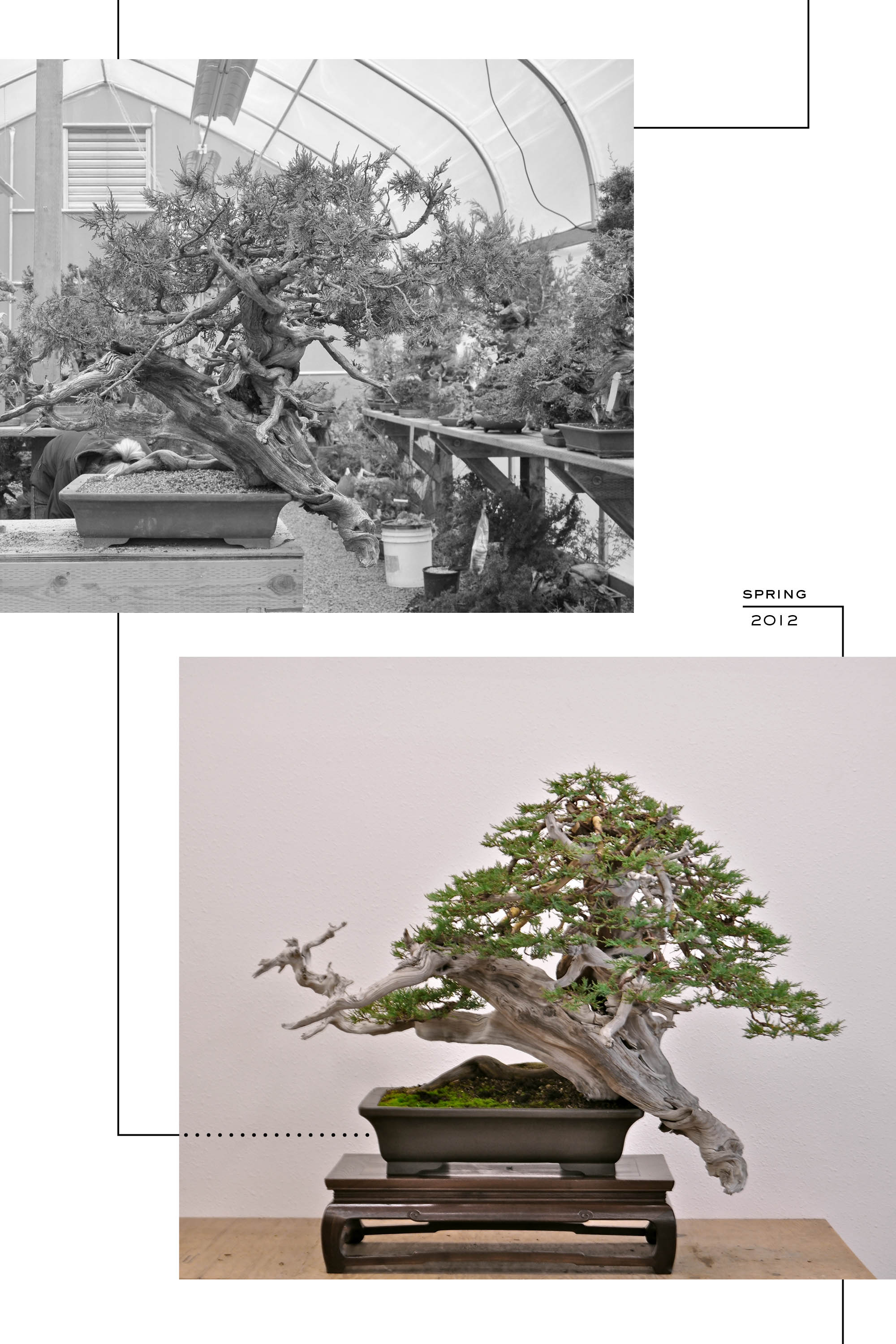

In the Spring of 2011, after I had come back from Japan and began building Mirai, Randy and I lugged Big Blue into the greenhouse to repot the tree out of its dilapidated wooden box. An operation like this is incredibly tenuous. This tree had been in this box out of collection for several years now. The tree was healthy, but not necessarily strong, and my margin for error was very small.

We dissected the roots carefully, exercising precise technique. We reduced some long roots and managed to get it into an incredible antique Japanese container. We were stunned, staring at such a unique, impressive tree. But we would have to wait another year for the tree to recover, imagining all the while what it could be once it was styled.

“This tree epitomizes struggle and survival; it was meant to be a bonsai.”

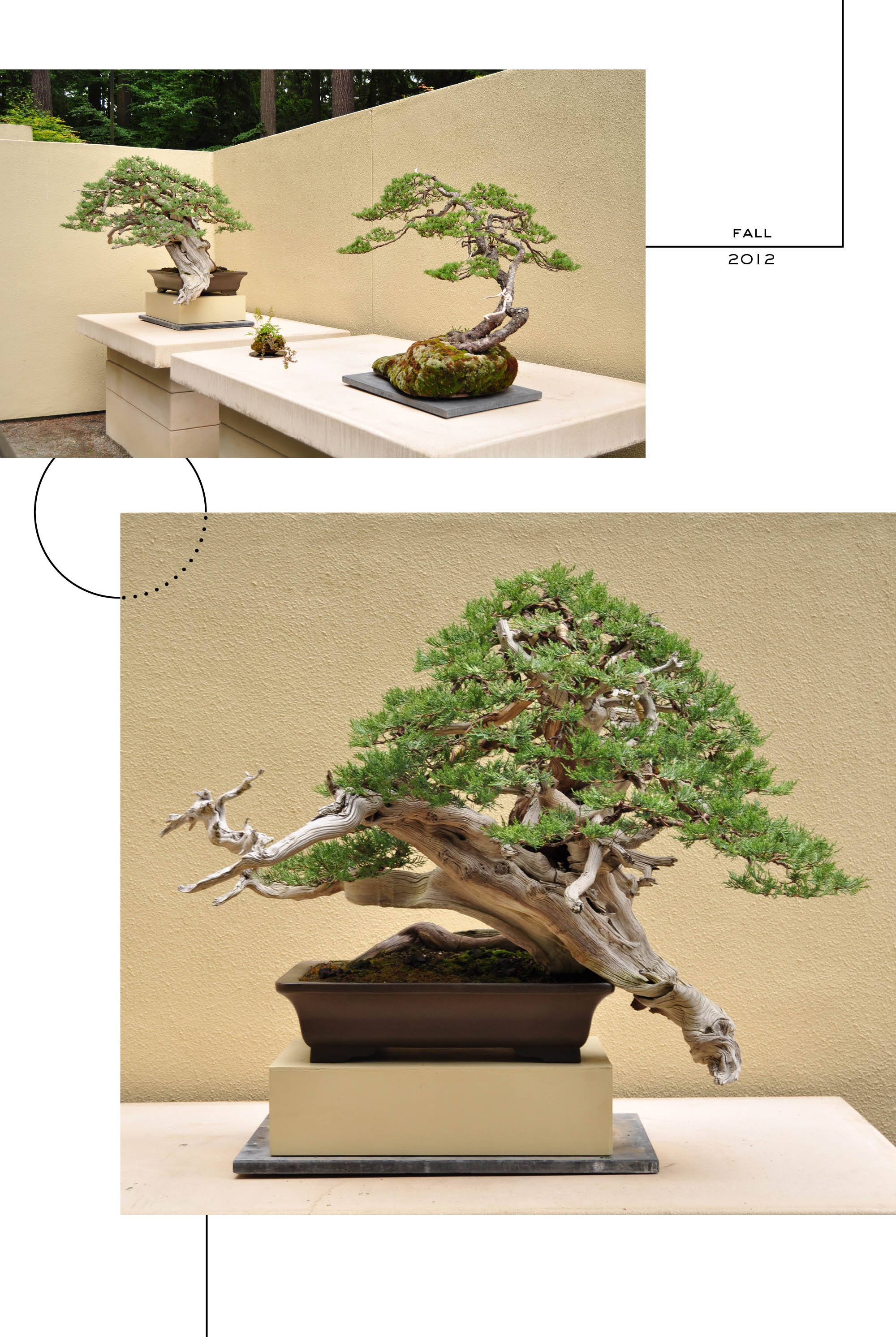

In 2012, we brought Big Blue into the workshop for its first styling. The initial design was very symmetrical in the foliage mass, but that order was contrasted by the dynamic movement in the trunk and deadwood. Even from the first styling, this tree embodied a nexus point in bonsai design, teetering between wildness and tradition.

“Even from the first styling, this tree embodied a nexus point in bonsai design, teetering between wildness and tradition.”

This tree was first exhibited in fall of 2012 at the ‘Weyerhauser Collection,’ which is now known as the Pacific Bonsai Museum. Even at that point, it was clearly a pillar composition for American Bonsai.

“It was bonsai engaging the viewer in a way that I had never seen before.”

“The journey with a bonsai is never finished.”

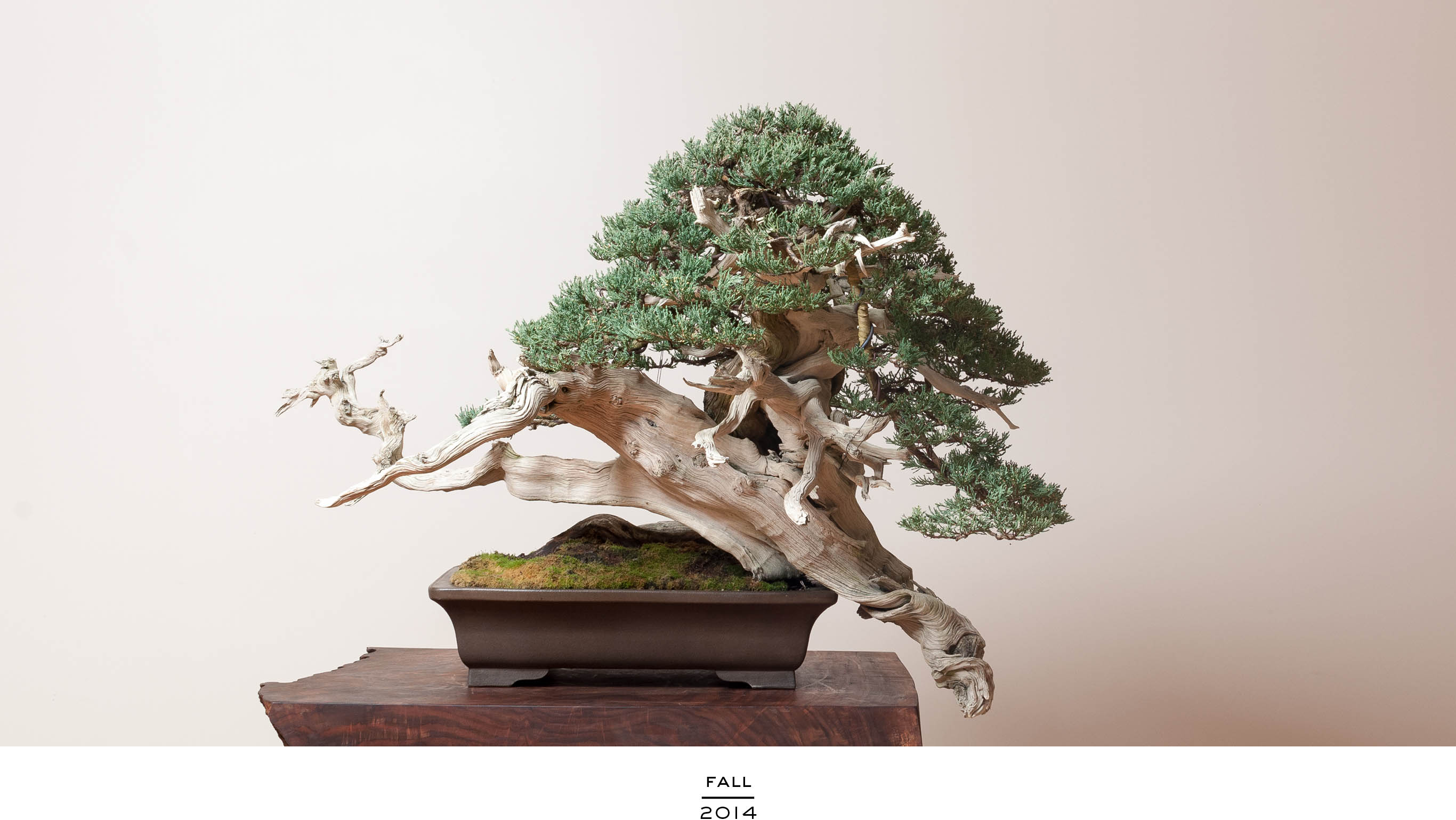

With time and further stylings, the asymmetry of the design expanded. For me, this was the first tree where I truly recognized the evolutionary process of developing a Rocky Mountain Juniper. Big Blue cemented the foundational reasoning behind my theories of the bonsai design process.

The first go, I started with the structure—this was my primary focus. I let the tree grow wild and recover, all the while increasing its secondary branching and strength. When the timing was right, both seasonally and in regards to the tree’s health, I wired out all the usable secondary branches to begin enhancing the design.

I then let the tree grow some more. With physiology and aesthetics guiding my way, I began seasonally pruning the vigorous growth on the tree to transition strength evenly throughout the branches and build fine tertiary ramification. This process has become our mantra at Mirai for juniper development.

The journey with a bonsai is never finished. In time, any tree gets to a point where it outgrows the valued proportions it once occupied. It becomes hard to see the brilliant characteristics we’d originally fallen so deeply in love with. These are moments to come back and further evolve the tree.

Big Blue continued to teach me how to progress bonsai design. By going back and removing several branches, I was able to create more negative space. This added to the visual age of the tree, while also pushing the degree of asymmetry. The composition began to represent an ancient form whittled by a harsh environment.

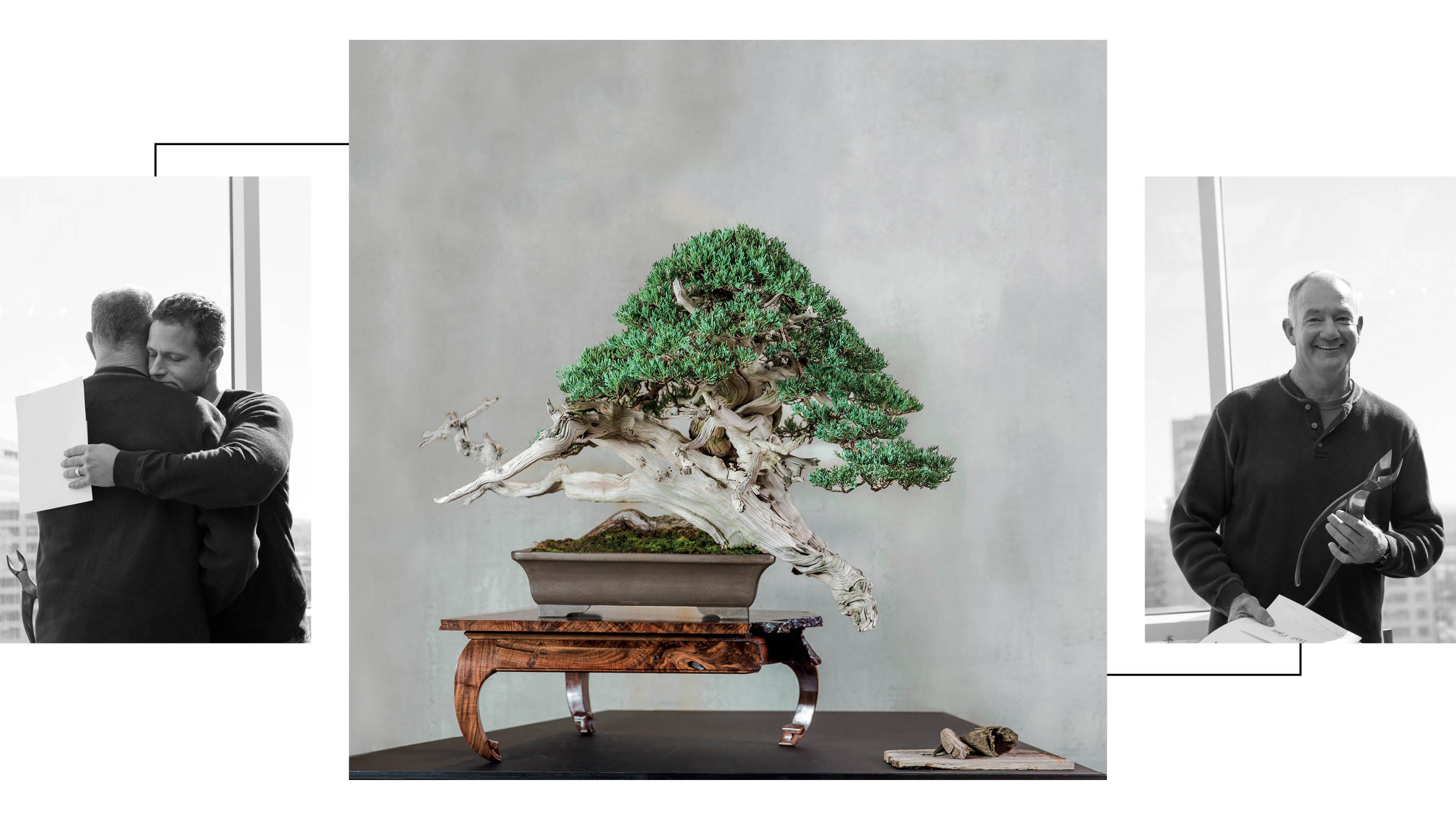

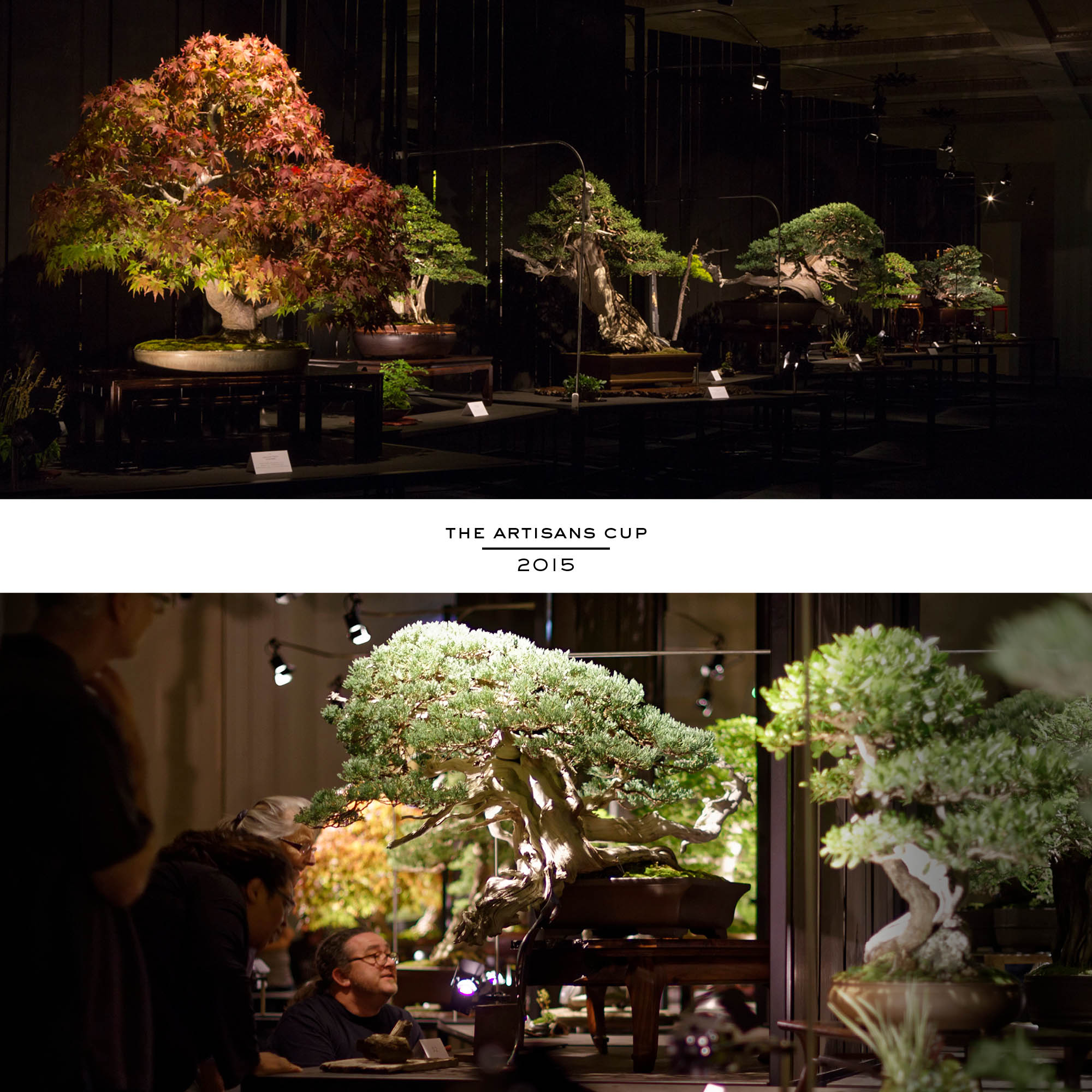

In 2015, Big Blue was finally reflecting the many years of work and consideration that I poured into it. As Randy was planning his display for the Artisans Cup, I suggested that he submit this tree. Recognizing Big Blue’s potential to have a major impact on people’s concept of native species, I contacted Austin Heitzman to collaborate on a stand that would elevate the tree’s unique characteristics. We came up with a design for a 3-legged stand, where the visual and physical weight of the cantilevered deadwood would hang over a decaying live-edge corner.

“Big Blue tests your understanding of what is possible with bonsai design, truly enhancing that emotive asymmetry.”

The resulting composition defies physics. As a viewer, your natural instinct is to search for stability, and Big Blue tests your understanding of what is possible with bonsai design, truly enhancing that emotive asymmetry.

The tree was glowing on display at the Artisans Cup, an incredible juxtaposition of avant-garde and more traditional forms. People attending the exhibition often crouched to explore the canopy of the tree. It was bonsai engaging the viewer in a way that I had never seen before.

Big Blue won the first prize in the inaugural Artisans Cup—an American Bonsai masterpiece. It is one of a select few, truly monumental trees that have evolved out of the American Bonsai Movement to reach a level of design that inherently deserves respect worldwide. And as a living, constantly changing being, this tree will continue to evolve, the asymmetry inherent in the ancient form growing stronger with the years.