Windy Ridge and Limber Pine Grove offer two dramatically different landscapes that tell parallel stories of overcoming harsh conditions in the Rockies.

The Rocky Mountains are the backbone of North America, forming a 3,000-mile continental divide from New Mexico to the northern boundary of British Columbia. The most extensive mountain system in North America, the Rockies, consists of over 184 peaks with elevations ranging from nearly 8,000 feet to over 14,000 feet. The eastern slope of the Rockies contributes almost half of the runoff that feeds the great Mississippi river and is one of two ranges that feed the 4th largest watershed in the world. To the west, the Colorado and Columbia rivers carry the abundant snowmelt of the continental divide to the oceans of the Pacific, giving rise to civilization in the arid Western United States.

The Rockies not only offer stunning diversity of terrain over its tremendous length, but the continual chain of imposing peaks is also home to many microclimates that house some of the oldest and rarest flora and fauna in the world. Over 900 species of plants, 200 species of birds, and an equally broad diversity of mammals are scattered throughout the oscillating ecosystems of the mountainous chain. The Colorado Rockies are home to 75% of the continental chain's highest peaks, creating radical diversity in exposure and elevation.

These primary circumstances set the stage for moisture-and temperature-driven communities of flora and their subsequent interaction with erosion, fire, and biodiversity. Understanding these contrasting elements in response to exposure informs the changing aesthetic of the environment and how it impacts the form of the mountain ranges' most ancient living organisms; the Limber pines of the Ancient Grove and the Bristlecone pines of Windy Ridge.

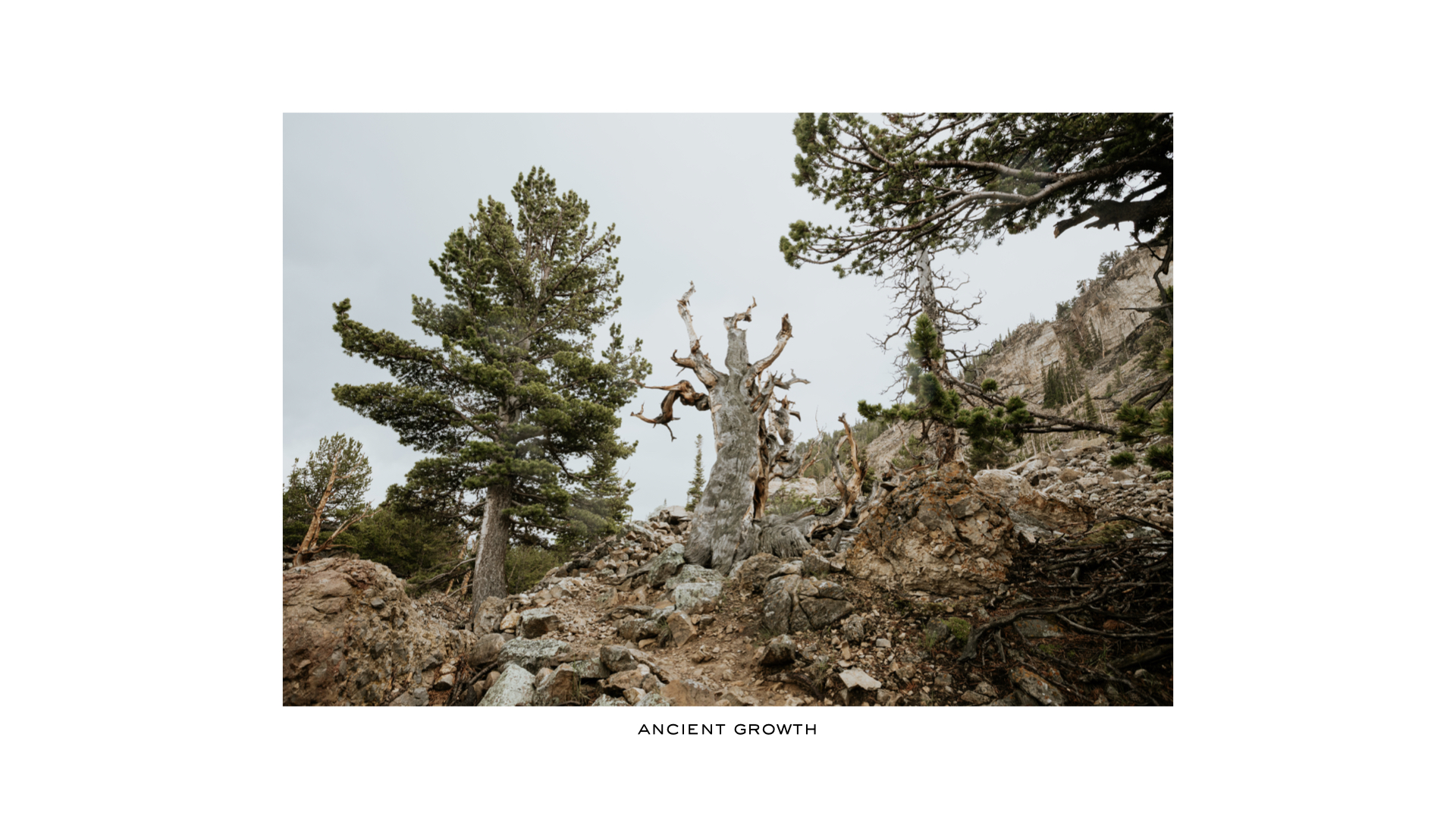

Within the more arid southern regions of the Rocky Mountains, extreme south and west-facing slopes experience pounding sun with intense ultraviolet rays that parch the landscape, making conditions impossible for all but the most durable, drought-tolerant species. In the Ancient Limber Pine Grove, the erratic, seasonal moisture and rocky geology create a sparsely populated patchwork of Limber pine (Pinus flexilis), whose solitary existence as the gladiator of Rocky Mountain flora has reached ages above 3,000 years.

The interspersed nature of the Limber pine is the key to success for the oldest trees occupying the Ancient Limber Pine Grove. Their sparse population and dispersed distribution make them far less susceptible to frequent, devastating fires that rage during drought-ridden summers. The rocky, wind-blown soils of the southern slopes are prone to constant erosion and intense dehydration. Consequently, there’s little chance for organic matter to accumulate and support a more robust vegetative ecosystem.

Despite the ruggedness, Limber pines thrive within these western exposed landscapes, free from competition with more rapidly growing, moisture-seeking trees in the more forgiving areas of the Rockies. Hidden behind the protection of stone and large topographic contours—Limber pines find shelter from the wind in low valleys where rain collects. Ancient Limbers have grown slowly and steadily in these rocky outcroppings for thousands of years by pushing their roots deep into dry aggregate soils.

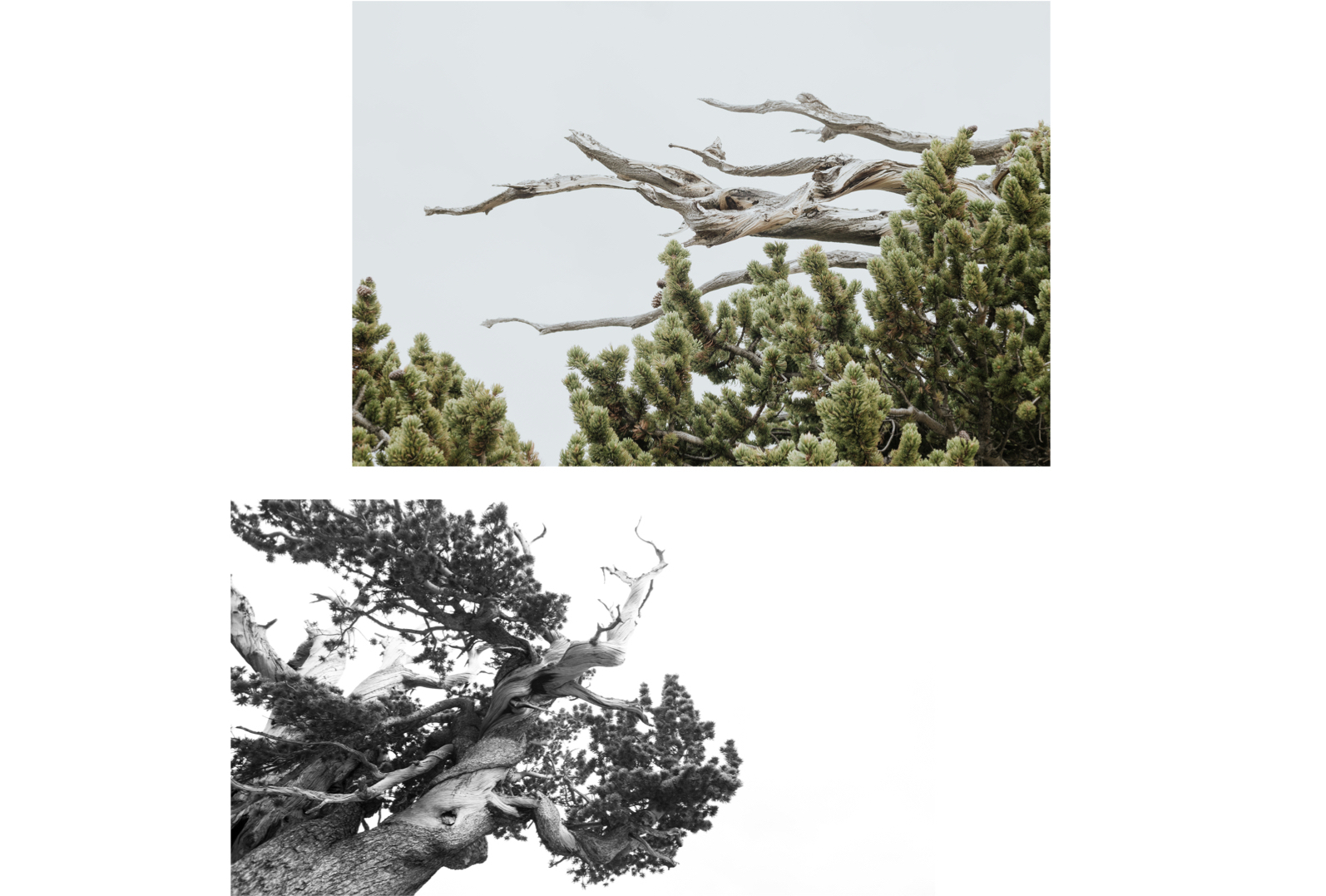

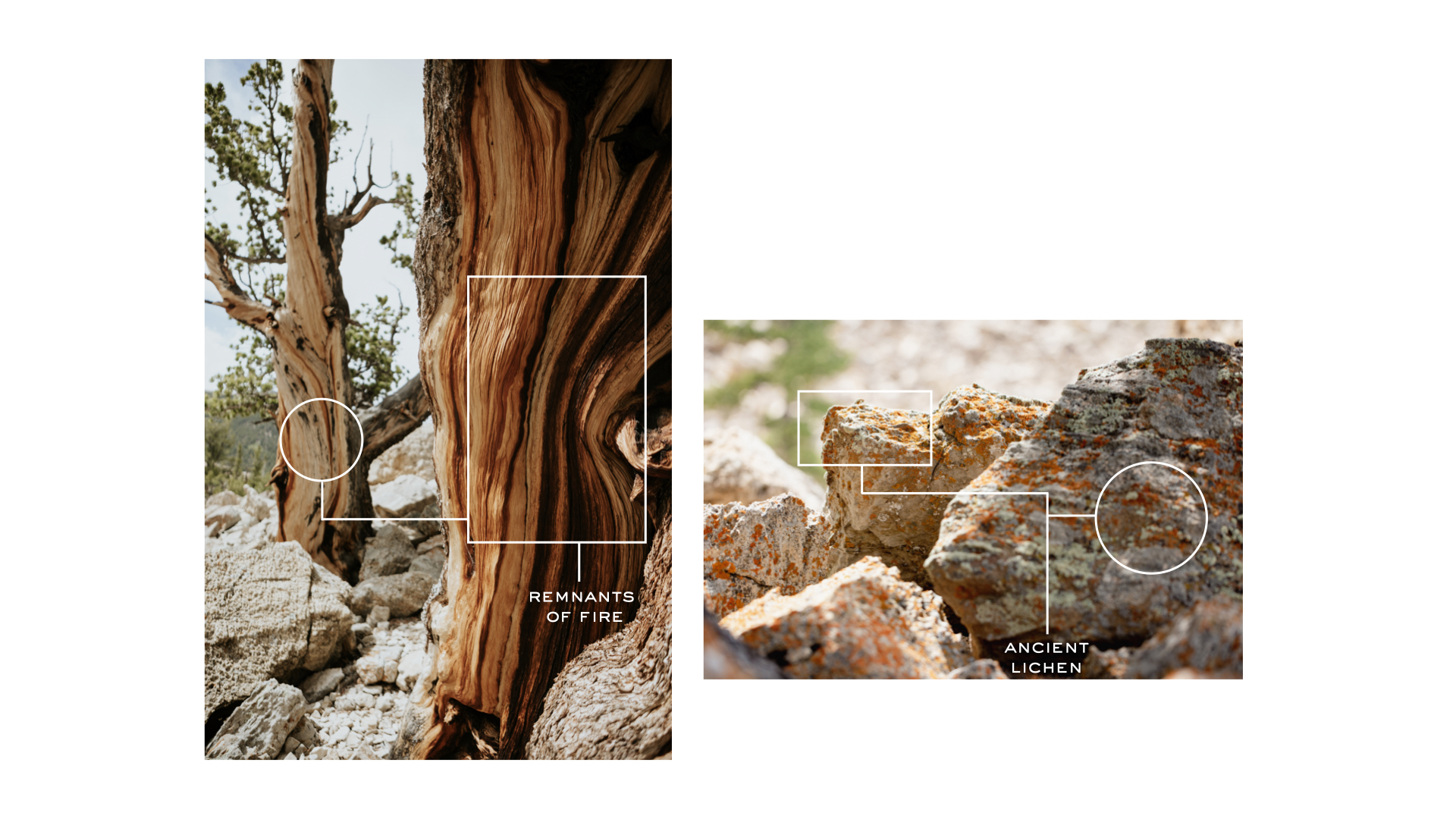

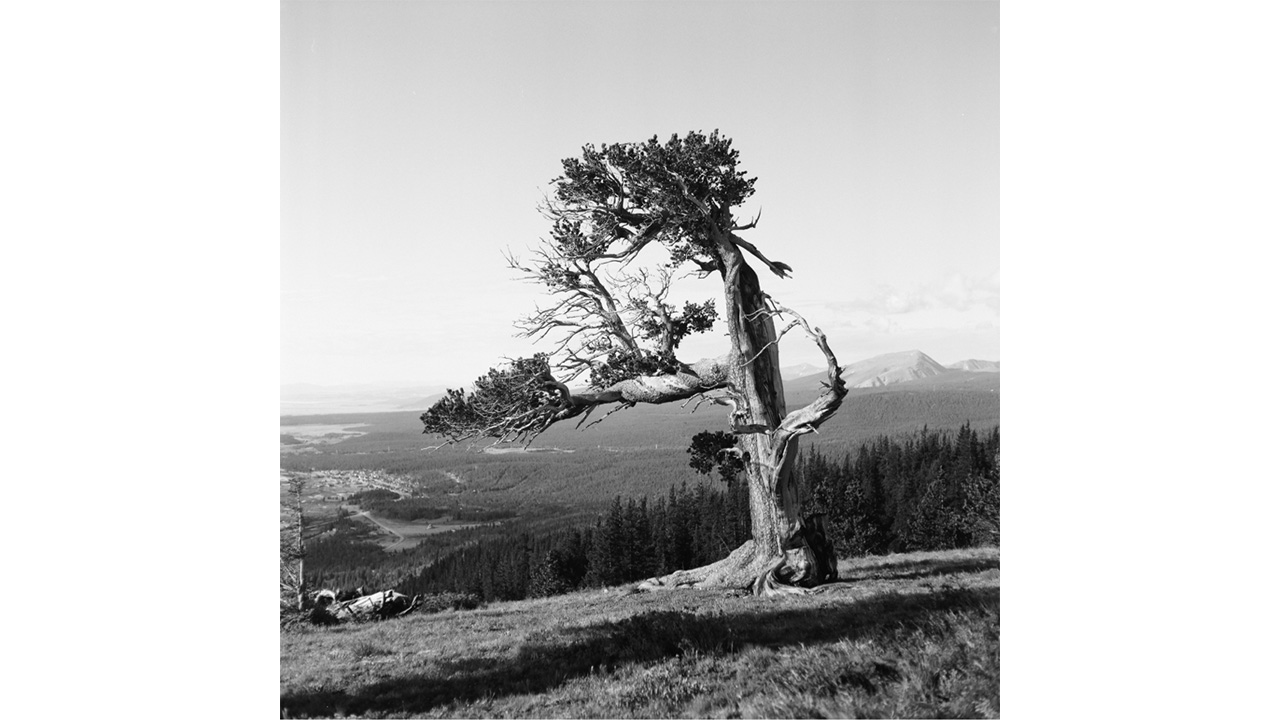

The forms of the ancient Limbers from the grove share nuanced similarities with the Bristlecone pines of Windy Ridge, both telling a similar tale of wind and exposure. The windward side of the pines has almost inevitably turned to deadwood, pitted and eroded by the blowing aggregate that sandblasts the living tissue into a petrified relic of what it once was. Downwind, the live veins of these ancient trees are protected by the hardened deadwood shells and bark so the veins can adequately support hydrating and nourishing the needle mass of the trees. Both pines have high resin content that fortifies life in extreme environments, not only by buffering moisture depletion but also by impeding insect infestations, fire, and the extreme cold that comes with life above 8,000 feet of elevation.

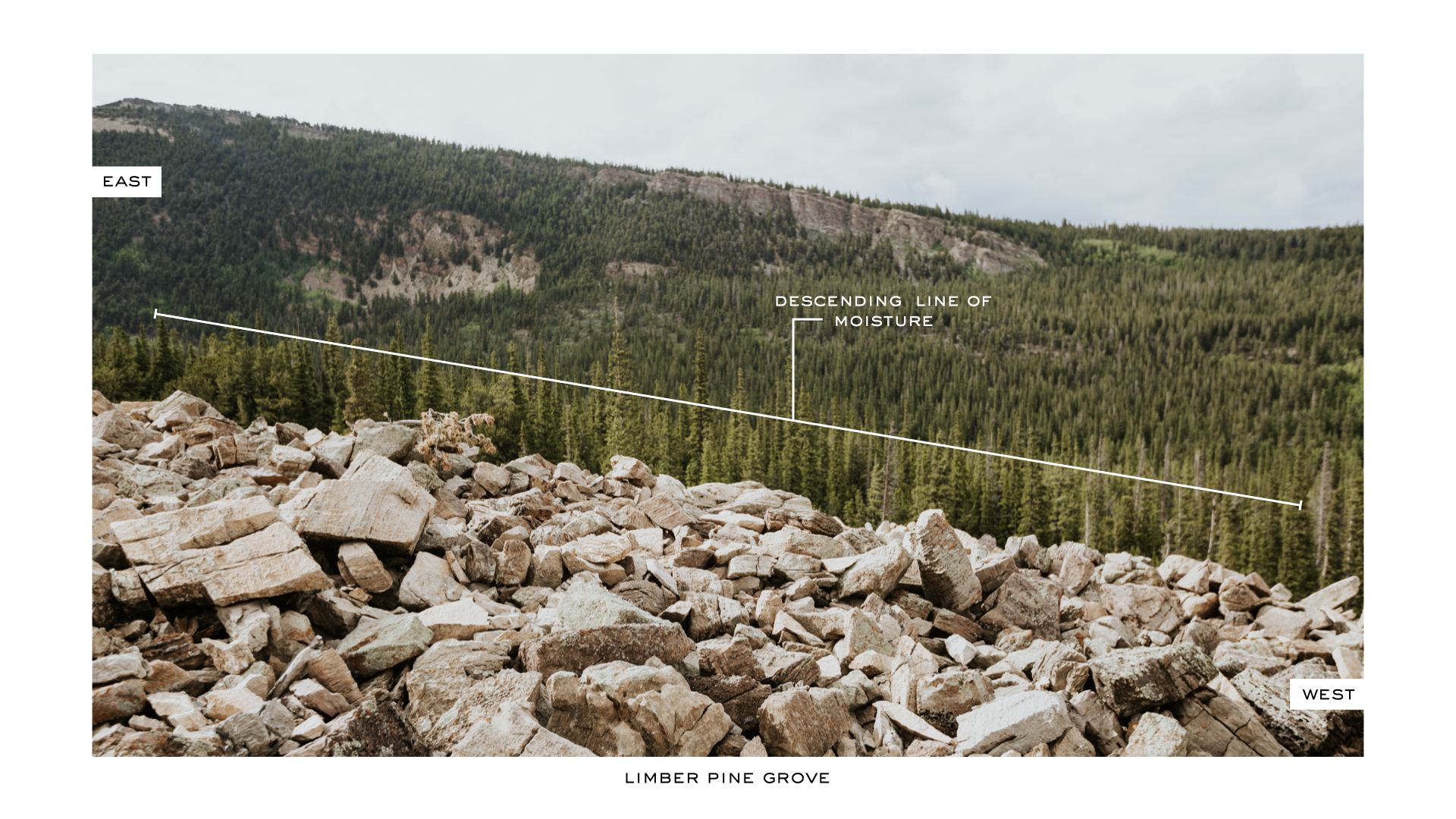

The flora occupying the varying slopes and elevations of the Rocky Mountains shifts as sun and heat exposure change the characteristics of the land mass.

South and south-western facing slopes in the Ancient Limber Pine Grove are windy, arid, rocky, eroding hillsides formed from direct exposure to the hot afternoon sun. The sun's desiccating force parches the land, causing oscillating moisture and temperature extremes, both of which break down the aggregate soils, further depleting them of water and nutrition. Life at 8,000 feet with intense exposure is barely tenable for the limber pines. It's as if they hold on to existence out of tradition, a staunch resistance to the harshness where equally ancient lichen is the only companion to these indomitable trees. Copious deadwood features openly display these trees' vulnerability to the land and its elements, while their needles and live veins exist in defiance of succumbing to its pressure.

Less than 40 miles as the crow flies to the east, the north-eastern facing slopes of Windy Ridge tell a radically contrasting tale of the trees and the environment. Shadier slopes of the east-facing ridge give rise to a perimeter of tall lush conical coniferous forests divided by a sparsely populated and interspersed landscape of wind-blown Bristlecone pine. Windy Ridge is one of only a few remaining Bristlecone Pine Groves worldwide. These ancient trees found their niche between 2000 and 3000 years ago when seeds sprouted in the sheltered exposure of the eastern slope and are still subject to the harshness of the Rockies. However, their experience is one of the differing extremes from the Limber pines surviving on the arid, rocky slopes of the Ancient Limber Pine Grove.

In contrast to the southern slopes of distant peaks within Windy Ridge, which are barren of organic vegetation, the eastern slopes are covered in wind-tolerant plants and forests protected from prolonged desiccating sunlight.

The depth of the Rocky Mountains and the continual backbone of undulating topography allows for a diversity of exposures made evident by the flora which occupies the various slopes that make up these incredible landscapes.

Both western and eastern exposed slopes in the Rocky Mountains are made of the same rocky aggregate foundation. However, slow-melting shady pockets of snow and prolonged runoff on less susceptible eastern slopes support and perpetuate larger plant communities. The abundant moisture fosters rapid foliar growth and rapid decomposition of seasonal plant debris on the forest floor. This moist, humic detritus generates a cyclical supply of organic matter that accumulates under mature trees and fosters seedlings in addition to a forest floor rich with plant diversity. Often, arid western slopes adjoin forested east-facing hillsides along the descending line of moisture where slope orientation shifts and runoff flows into streams or rivers.

The familiar site of fire-lapped trunks in the Ancient Limber Pine Grove is a testament to the consistent threat all trees in the Rockies experience. Summer thunderstorms prey on heavy fuel loads that result from lush spring growth drying out over prolonged periods of intense sun and no precipitation. The Rockies sit on the boundary of an already arid, high-desert region caused by rain shadows from the Sierra and Cascade mountains to the west—the central continental location truly impacts the state of drought in the Rocky Mountains.

During summers, when the jetstream, carrying moist air off the Pacific, stays north, the Rockies become a tinderbox waiting to explode. Only the aridest and sparsely populated forests survive nature's fiery wrath. The Ancient Limber Pine Grove exists both in defiance of and due to its severe orientation and inhospitable exposure, where only lichen can accompany such resilient trees.

Given a choice, Limber pine is not necessarily preferable to arid, rocky conditions in the western exposed Rocky Mountains—yet they manage to take root despite the lack of moisture, free from competition with the most robust genetics to survive and proliferate. For millennia, Clark's nutcracker has dispersed Limber pine seeds amongst exposed outcroppings, concealing their seeds in areas where snow won't accumulate throughout the winter. These seed caches provide food throughout the harsh winter months and aid in forming the sparse distribution that has allowed Limber pine to persist.

Approximately one in every million limber pine seeds might germinate and live to a hundred years, while one in every trillion may mature into an ancient tree. As these trees survive in inhospitable environments, it is easy to witness how intelligent and resourceful they can be.

Ancient is a story of exposure, distribution, and scale. In regions starved of essential resources such as moisture, trees grow older and more prominent because they were fortunate enough to be deposited in a location with dependable moisture. Conversely, moist periods may cause moderate or evenly sparsely hydrated areas to be favorable for germination and decades of growth. Even during extended droughts, the Limber Pine Grove sustains rare pockets of life, telling a story of time throughout the landscape.

Sentinel trees in the Ancient Limber Pine Grove have existed for thousands of years. These trees have witnessed hundreds of fires and been burned many times but refuse to succumb to the elements. Desiccation of the tissue, sun, erosion, and wind influence their shapes. This environment is harsh. But the aridity creates independence, a natural selection of the strongest and fittest, giving space to the victor to rise to such antiquity.

The line that divides young and old is the same mark that defines topographical shifts in exposure and orientation. The youthful forest of the east-facing slope provides an expansive narrative that contrasts the ancient Limber of the western slope. The dense, fickle forest of youth grows fast and without wisdom, forgetful of the fire that recently burned its ancestors.

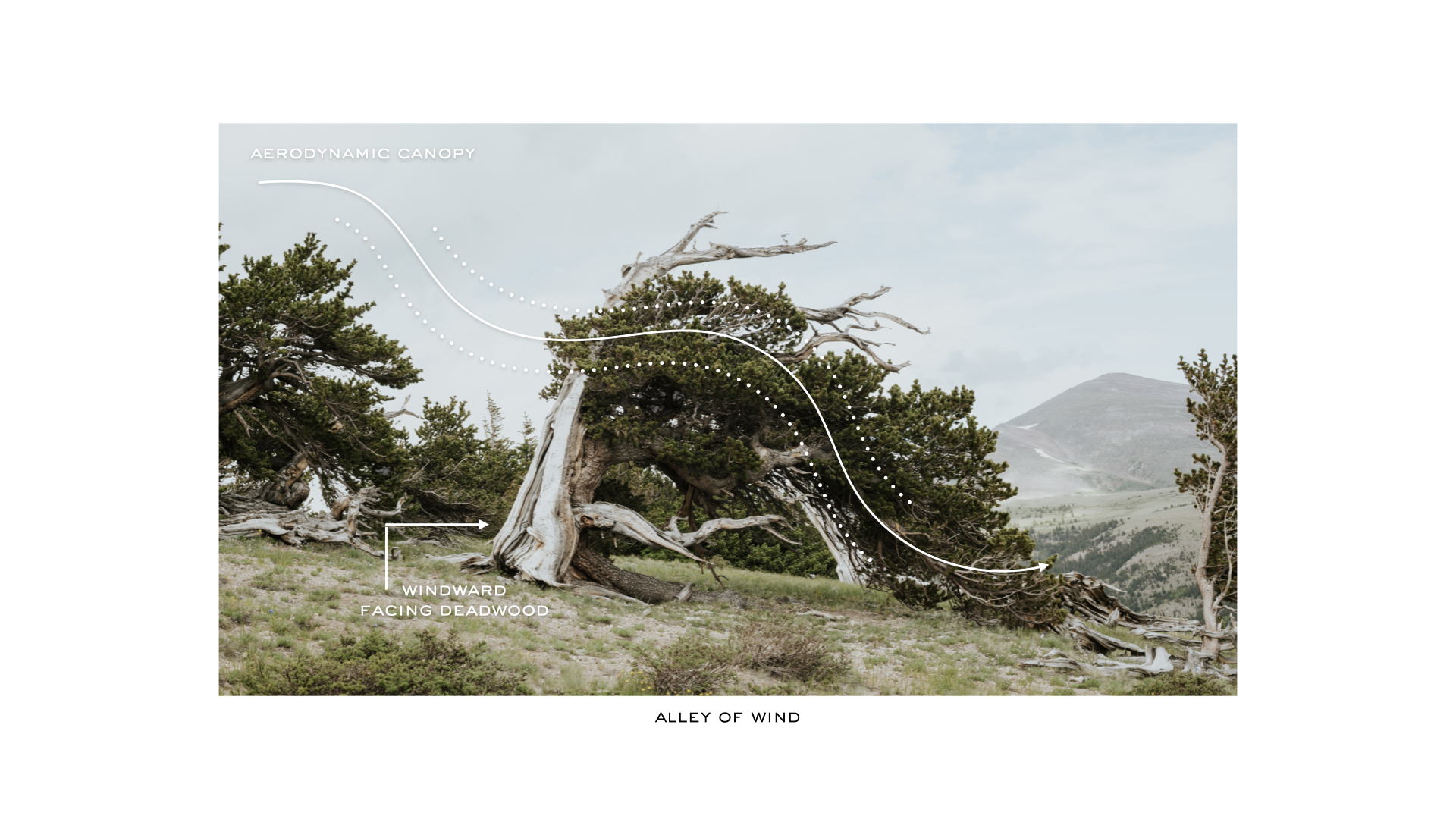

The Bristlecone pines of Windy Ridge found their niche on east-facing slopes in windy pockets and outcroppings. For thousands of years, these pines have grown in organized groupings guiding the wind over and around the densest regions of their canopy, one tree providing shelter for another. The knoll of Windy Ridge is subject to focused winds concentrated by the surrounding high peaks and local topography, forming a natural wind tunnel. Routinely, these Bristlecone pines endure gale force storms when Chinook winds develop from warm air cooling as it climbs the mountainous slopes. As a result, Bristlecone pine would have little to no chance of competing with the more robust and rapidly growing alpine conifers in the more sheltered areas in the surrounding landscape. Still, their durability empowers these ancients to occupy a harsh but unfettered existence in the narrow, wind-influenced ridge free from competition.

On good years, the plant communities of Windy Ridge get a luxurious trickle of moisture through the summer as cornices and shady snow patches melt. With reduced sun intensity and increased moisture availability on the eastern slope, it's easier to imagine the Bristlecones could tolerate such intense winds and survive. Indeed, they could not grow fast enough to exist in the mixed forest. The compounding conditions of the environment and the elements form the perfect pocket to support their prolonged existence in the Rocky Mountains landscape.

The biting cold and continual wind are factors that most inform and sculpt the statuesque sentinel pines, but bristlecone pines are not the only notable shift in flora on Windy Ridge. The moist understory and surrounding forests are lush and vibrant with flowering perennials and the conical form of alpine conifers. The rich understory's varying shades of plant life provide beautiful color and contrast throughout the changing seasons. This moisture-driven existence is an entirely different plant community and aesthetic response that only comes with less severe exposure to the high-altitude sun.

Bristlecone pine and Limber pine are closely related and tolerant of similar conditions—making the contrasting environments of these two ancient groves all the more intriguing. Instead of arid hillsides, the eastern slope of Windy Ridge is defined by the wind as the isolating condition that creates the interspersed forest of tortured ancient Bristlecone pine.

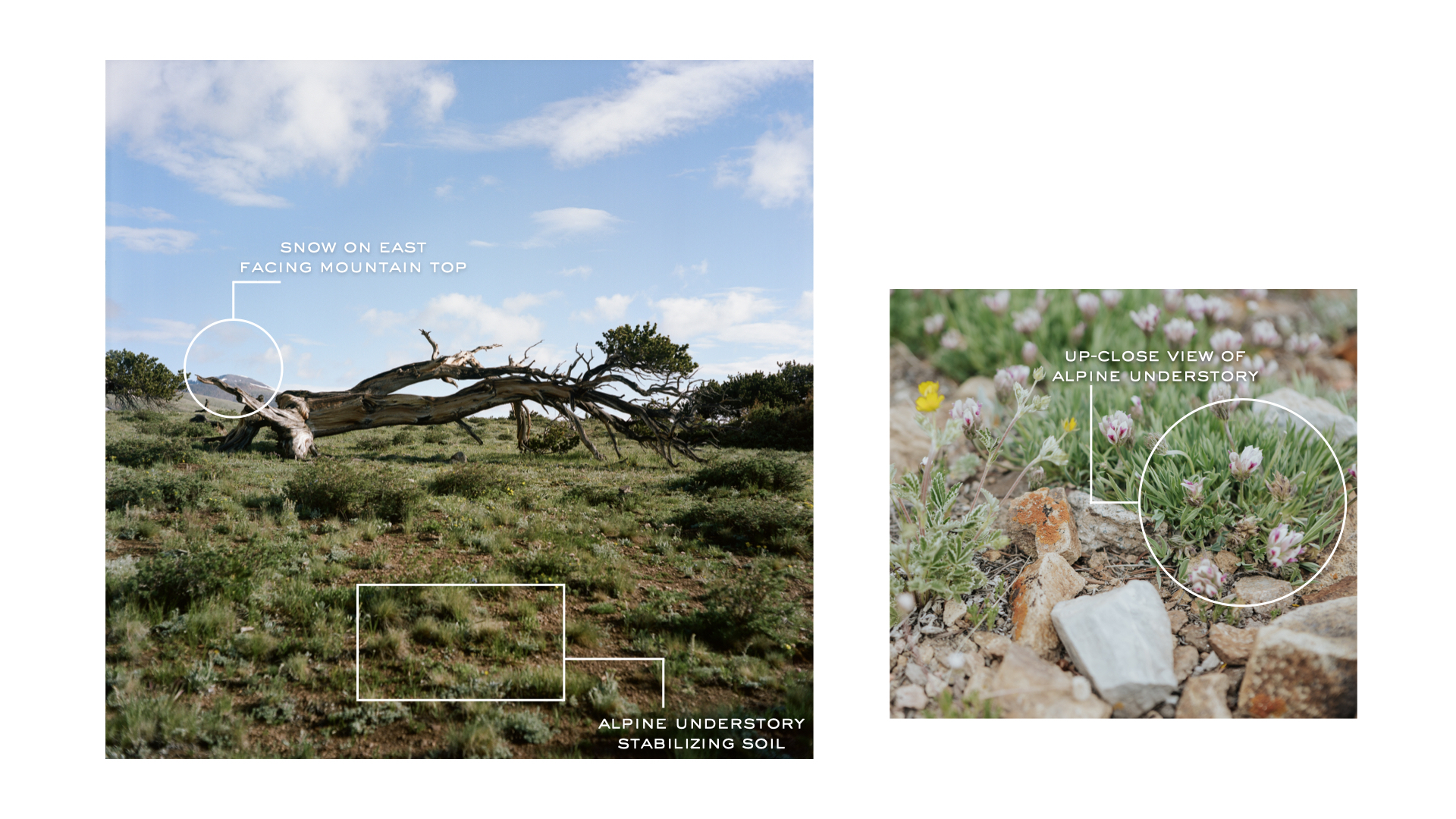

Observing the form of the tree is akin to reading a book that explains the landscape and all the elements acting on it. Distant peaks form natural contours that shelter dense, youthful forests beneath their crests of protection. Shady patches of snow, still present in mid-summer, continue to supply a slow, steady stream of moisture to tall lush forests of mixed conical conifers. The sheltered eastern slope provides ample protection from the harsh exposure of the alpine sun.

Meanwhile, a break in the dense conical forest gives rise to an open alley, sparsely populated with ancient wind-toppled and tortured Bristlecone pine. Depressions between distant peaks unveil a vacant meadow, destitute of mature plant life until the topography drops over the edge of the slope. As the wind funnels through the deadwood, linear colonies of ancient Bristlecone pine become compelling gestures that convey their contours and survival lessons. The trees in both circumstances are clear orators of their individual experiences in the alpine landscape of the Rockies.

The wind informs every aspect of the shapes Bristlecone pines become on Windy Ridge, including the form of their roots. Over time, wind erodes the living tissue on the windward side of the pines, altering the superstructure of the tree and its ability to stay upright. Deadwood gives way to the force of the wind, and the dead tissue snaps under the sail effect of Chinook winds crashing into the canopy. The broken roots of the toppled pine show smooth, wind-eroded remnants of torn tissue that used to anchor the trunk to the ground. The living vein acts as a foundation on the leeward side, sheltered from the wind's destructive erosion, where it digs deep into the ground like a pylon supporting a building. The branching is erratic and irregular, bending against convention to the wind's whim. Environments like Windy Ridge, which allow for unique pockets of profound conditions, are occupied by ancient trees, not because of the comfort they provide; but instead the ruggedness they demand. This resounding force continuously acting on these trees alters their state of existence and the elements they must adapt to as their position and stability in the ground are continually compromised.

While Bristlecone pines survive as individuals, there is an undeniable symbiosis tree to tree in how the canopies have taken on a universal rhythm of the wind. Following the undulating lines of the alleyways of pines, it is effortless to see how the wind has reprimanded non-conforming growth, stripping outlying branches of foliage and bark, leaving behind ghostly remains of deadwood as a lesson to growth tips who dare veer out of line. Each alley's lead tree is toppled, its windward side stripped of living tissue, roots broken, and lying prostrate. The successors in line gradually stand increasingly erect as each tree buffers the impact of the wind on its successive neighbor until the alleyway terminates with an upright Bristlecone showing the effects of wind only in its highest branches.

The lushness of this region is apparent in the understory with the present snow on the east-facing mountaintops. Moisture necessitates high alpine plants to decorate and stabilize the soil. This area was once aggregate, but millions of years of eastern exposure gave rise to dirt, organic matter, moisture retention, and limited erosion.

This tree was once the root that held the ecosystem together. With its deteriorating carcass clinging to life with a thread, it nurtures beautiful flowering, highly moisture-dependent plants. So goes the cycle of life on the eastern slope. Every orientation has an exposure, and every direction showcases a different rhythm to life and death.

Despite occupying neighboring mountainous slopes, the Limber pines of the Ancient Limber Pine Grove and the Bristlecone pines of Windy Ridge remain subjects of contrasting extremes. If proximity in the Rockies defines regional character, then orientation determines survivability. Finding their niche in opposing conditions demonstrates the adaptability and durability of these profound trees and the environments they symbiotically exist in. These ancient organisms are the greatest orators of the native environment, giving rise to every other living thing that exists among them and communicating the deepest secrets of their landmass. If we look and listen hard enough, they tell us a rich history we’d otherwise never uncover.